Summary: Bible translation began early in the Christian era as part of the way to fulfill the Great Commission. But it wasn’t an easy road to get to today, where we have over 50 English Bible translations to choose from.

Then Jesus came to them and said, “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Therefore, go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you. And surely I am with you always, to the very end of the age.” – Matt 28: 16-20 (NIV)

It’s All Greek to Me

Do you have a favorite version of the Bible? Have you ever heard someone say that they only read a certain version? Is there a “right” version? How did we even get so many versions to choose from? With over 50 English translations available, how is one to choose? To give you a little help in that matter, here is a brief history of the translation of the Bible.

Bible translation has always been an important part of God’s mission. We are told to hide God’s word in our hearts in Psalms 119:11, but to do that we need to first know his word. The original biblical texts were written in Hebrew, Greek and Aramaic but if you speak English like me, you will need to choose an English translation of the Bible so you can read it.

Jesus’ last command to the disciples was “Go into all the world and preach the Gospel” (Mark 16:15). Writing the good news down and passing it around was a perfect way to accomplish this command. Most of the New Testament books were letters written to specific churches that were copied over and over in Greek and distributed.

Translation from Greek into other languages began very early on in the Christian era, around AD 170. The first language New Testament texts were translated into was Syriac, the language spoken in Damascus. Ironically, the very place Saul went to persecute the church in Acts 9 was the first to have the Scriptures in their native tongue, after Greek-speakers.

Over the following centuries Bible translation spread out from Syria into Armenia, Georgia, Samarkand and beyond. The Septuagint was almost always the source used for Old Testament passages at this beginning stage. The Septuagint was a Hebrew to Greek translation that was completed around 130 BC for Greek-speaking Jews. This is the version Paul most likely used when quoting from the Old Testament.

Jerome and the Latin Vulgate

As language changed, new translations needed to be written. Around AD 382, in an effort to make the Scriptures once again available to ordinary people, the Pope commissioned his secretary Jerome to create a new translation in Latin. With great seriousness and trepidation, Jerome accepted the task. He was passionate about this assignment and tradition credits him as saying, “ignorance of Scripture is ignorance of Christ.”

He learned Hebrew and was able to access biblical texts in both Hebrew and Greek, thanks to the works of Origin. Jerome’s finished product is what we call the Vulgate. Many of our biblical terms in English such as, Scripture, salvation, justification and regeneration, come from this version. The Vulgate Latin Bible became the standard used by the Roman Catholic Church for 1,000 years.

John Wycliffe and the First English Bible

Efforts to translate the Bible into Old English (Anglo-Saxon) began in the 8th century, first with the book of Psalms and then the Gospel of John. Other parts were translated as well, but these efforts were brought to a temporary halt with the Norman Invasion of England in 1066.

In the 14th century, Oxford teacher and priest John Wycliffe challenged the growing power and privilege of the Catholic Church, which was now firmly anchored in the long held tradition of the Latin Vulgate. Wycliffe began translating the Bible to Middle English, the common language, so Christians could read it for themselves without having to depend on the Church. His followers completed the task and nearly 200 copies of his manuscripts have survived.

Unfortunately, the early missionary perspective on Bible translation had shifted dramatically. The leaders of the Church now thought only learned scholars and men of intelligence should have access to the Bible. Consequently, forty-four years after Wycliffe’s death, the Catholic Church officially excommunicated him. His body was dug up, burned, and dumped into a river.

Nevertheless, Wycliffe’s vision spread through Europe inspiring the Czech priest and philosopher Jan Hus and others to produce Bible translations in Hungarian and Bohemian. As a result, in 1415 Hus also was declared a heretic and burned at the stake.

William Tyndale and the First Printed English Bible

With the invention of the printing press in the 15th century, Bible translation changed radically. William Tyndale was an English chaplain, tutor and scholar who worked on the first printed English translation of the New Testament in 1526. This iconic translation would form the base for most future translations.

Tyndale had a gift for language and was able to communicate powerfully. He coined many common phrases including: ‘land of the living,’ ‘the parting of ways,’ and ‘apple of my eye.’ He worded the familiar verses, ‘fight the good fight,’ and ‘the spirit is willing but the flesh is weak.’ The word ‘at-one-ment’ was his invention and his use of the archery term for missing the mark, ‘to sin,’ was ingenious.

Sadly, of the 3,000 copies of the New Testament Tyndale printed, only two have survived, due to the Catholic Church of England’s active suppression and burning of the books.

Around 1529, Tyndale began a translation of the Old Testament in Europe. By 1535, he had finished the Pentateuch and nine other Old Testament books when he was captured and burned at the stake. His last words are reported to be: “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes.”

Coverdale, Matthews, and The Great Bible

Miles Coverdale continued Tyndale’s effort and finished the printing of the first complete English Bible in 1535. Not being proficient in Greek and Hebrew, he used Latin and German translations, as well as Tyndale’s unpublished works, including his partial Old Testament. In the preface of the Bible, Coverdale praised King Henry VIII, who on account of his new Queen, Anne Boleyn, had split with the Catholic Church of Rome and set up a Church of England. The Coverdale Bible was the first Bible licensed by King Henry VIII for use in England. Later Coverdale was authorized to translate The Great Bible of Henry VIII in 1539.

Other translations followed with the goal of keeping the language common and being more accurate to the original Greek and Hebrew. John Rogers, a friend and editor of Tyndale, incorporated Coverdale’s work and produced the Matthews Bible in 1537. In the latest wave of back and forth violence, the new Queen Mary went on a rampage to return England to Catholicism, and Rogers was burned at the stake for being a Protestant in 1555.

The Geneva and the Catholic Rheims-Douai Versions

Because of persecution, hundreds of Protestants fled to areas in Germany and Switzerland, especially Geneva, where eventually the Geneva Bible was produced in 1560. This contemporary English version accomplished many firsts. It was the first to use a team of translators, number verses, have commentaries in the side margins, and contain maps and illustrations. The Geneva Bible was the most accurate version at the time and became the primary Bible of 16th century Protestantism.

When Queen “Bloody Mary” was succeeded by her sister Elizabeth I, an updated version of The Great Bible was created as an attempt to compete with the popular Geneva Bible. A panel of bishops prepared this translation in 1568, aptly calling it the Bishops’ Bible; nevertheless, the Geneva Bible continued to be the most popular version in England.

Then finally, in 1582, the Catholic Church who had fought so hard to keep Latin as the only language for the Bible, beside its original sources of Hebrew and Greek, produced its own complete English translation from the Latin Vulgate Bible called the Rheims-Douai Bible.

The King James Version of 1611

In 1603, King James VI of Scotland assumed the throne of England as King James I of England, and during an ecclesiastical conference at Hampton Court it was decided that a new Bible translation needed to be made to replace Elizabeth I’s Bishops’ Bible. Problems among Protestants, Catholics and new denominations were emerging and the goal was to make a scholarly version of the Bible for all Christians to be able to use.

The plans for the King James Bible were elaborate. A group of 47-54 translators were gathered and given 15 rules as guidance. The Bible was not to include Geneva Bible type commentaries. The translators were to base their work on the Bishops’ Bible, but the other major English versions were also considered and the whole was corrected from original Hebrew, Greek and early Latin texts. The translators were divided into six companies with each company assigned specific books. Completed translations were sent to other companies for review and the final needed agreement among all translators.

The KJV Bible was not immediately popular but in 1660, with the restoration of the English monarchy under King Charles II, public fondness for the king was rekindled. The KJV eventually gained widespread popularity in England, the Anglican Church, and the American colonies.

Genesis 1 Translations Comparisons

John Wycliffe Bible 1384

In the firste made God of nouȝt heuene and erthe. The erthe forsothe was veyn with ynne and void, and derknessis weren vpon the face of the sea; and the Spiryt of God was born vpon the watrys. And God seide, Be maad liȝt; and maad is liȝt.

William Tyndale Bible 1529

In the beginnyng God created heauen and erth. The erth was voyde and emptye, and darknesse was vpon the depe, & the spirite of God moued upon the water. Than God sayd: let there be lighte and there was lighte.

Geneva Bible 1560

In the beginning God created ye heauen and the earth. And the earth was without forme & voyde, and darkenes was vpon the depe, & the Spirit of God moued vpon the waters. Then God saide, Let there be light: And there was light.

Conclusion

The good news of the Bible was meant to be shared and read by everyone, just as Jesus went out of his way to include outcasts and lowly people. To best understand God’s word each person should have it in their native language. The missionary work of producing versions of the Bible for all people was a hard fought battle, but with persistence and God’s help it moved forward.

We must be thankful for the abundance of English versions we have to choose from which allow us to best understand the original Bible. Plus, we are beyond blessed to have access to the earliest Hebrew and Greek texts online. As language inevitably changes throughout time, Bible translations need to as well, to best follow the ultimate goal of spreading God’s word of forgiveness and hope in a way that each person can understand.

Keep Thinking!

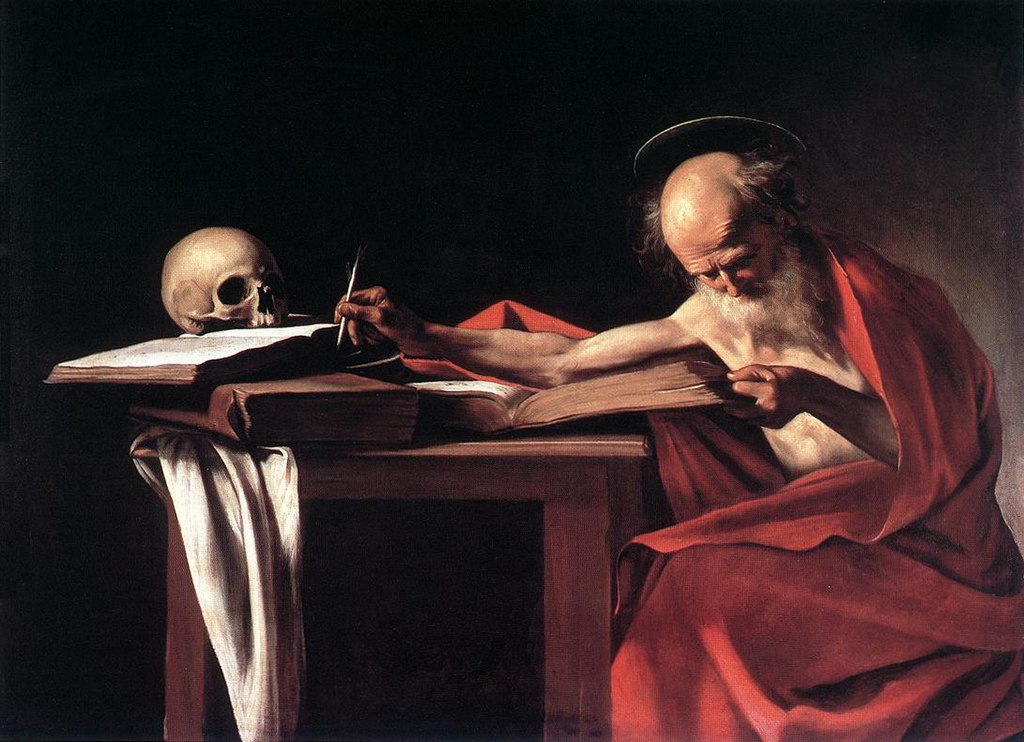

TOP PHOTO: Saint Jerome Writing, 1606. (credit: Caravaggio, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)