Summary: A rare, almost 2,000-year-old, detailed paycheck of a Roman soldier, who took part in the siege at Masada, reveals he wasn’t in it for the money.

But the centurion replied, “Lord, I am not worthy to have you come under my roof, but only say the word, and my servant will be healed. For I too am a man under authority, with soldiers under me. And I say to one, ‘Go,’ and he goes, and to another, ‘Come,’ and he comes, and to my servant, ‘Do this,’ and he does it.” When Jesus heard this, he marveled and said to those who followed him, “Truly, I tell you, with no one in Israel have I found such faith. – Matthew 8:8-10 (ESV)

Detailed Deductions Down to Zero

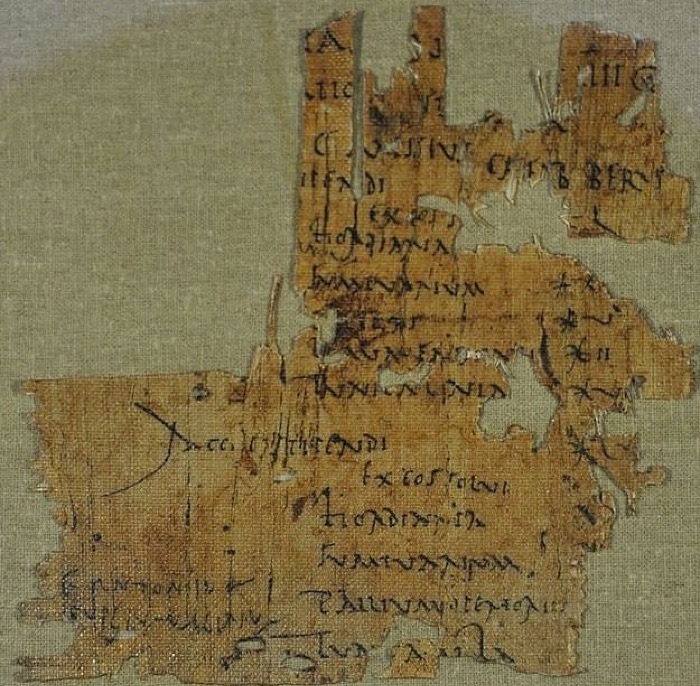

Archeologists have discovered a Latin papyrus with a detailed paycheck of a Roman legionary soldier at the Masada fortress in Israel. The ancient scroll is dated to AD 72, two years after the destruction of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem, during the time of the Great Revolt of the Jews against the Romans (66-74 AD). The evidence shows that enlisting as a soldier in the Roman Legion wasn’t quite as profitable as one might imagine.

This find along with the story of Rome’s crushing of the Jewish rebellion gives us unique insight into the political realities in Israel during the 1st century of Jesus’ time. The overwhelming power of the Roman occupiers fed the feeling of hopelessness among the Jewish people and their desire for a savior who would bring justice.

The rare scroll is considered the best-preserved Latin papyrus from Masada and one of only three legionary paychecks discovered in the entire Roman Empire, according to the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA). The invaluable scroll is part of a unique collection of at least 14 Latin documents unearthed in various states of preservation, 13 written on papyrus and one on parchment.

The papyrus paycheck contains important information about the management of the Roman army and the status of its soldiers, revealing that soldiers were not compensated well by Rome. Although the fragment is damaged, the details of a Roman soldier’s salary, including various deductions he was charged, can be deciphered. The summary covers two out of the three paychecks a soldier would receive each year.

The pay slip was made out to Gaius Messius and was found in an area where Romans set up camp during the Masada siege. It is dated to a time after the war, suggesting it was payment for participation.

“Surprisingly, the details indicate that the deductions almost exceeded the soldier’s salary. Whilst this document provides only a glimpse into a single soldier’s expenses in a specific year, it is clear that in the light of the nature and risks of the job, the soldiers did not stay in the army only for the salary,” said Dr. Oren Ableman, senior curator-researcher at the IAA Dead Sea Scrolls Unit.

A soldier was provided with basic equipment from the Roman army, but any upgrades or additions to their gear came out of their own pocket. “This soldier’s paycheck included deductions for boots and a linen tunic, and even for barley fodder for his horse,” Ableman continued. The total deductions add up to 50 denarii, the soldier’s entire paycheck!

The translation of the document is available in the Database of Military Inscriptions and Papyri of Early Roman Palestine. It reads:

- The fourth consulate of Imperator Vespasianus Augustus.

- Accounts, salary.

- Gaius Messius, son of Gaius, of the tribe Fabia, from Beirut.

- I received my stipendium of 50 denarii,

- out of which I have paid

- barley money 16 denarii. […]rnius;

- food expenses 20(?) denarii;

- boots 5 denarii;

- leather strappings 2 denarii;

- linen tunic 7 denarii.

Supplemental Side Hustles

To supplement their meager income, “the soldiers may have been allowed to loot on military campaigns. Other possible suggestions arise from reviewing the different historical texts preserved in the IAA Dead Sea Scrolls Laboratory,” Ableman said.

“For example, a document discovered in the Cave of Letters in Nahal Hever from the time of the Bar Kokhba Revolt (132–135 CE) sheds some light on some side hustles Roman soldiers used to earn extra cash,” he continued.

“This document is a loan deed signed between a Roman soldier and a Jewish resident, the soldier charging the resident with interest higher than was legal. This document reinforces the understanding that the Roman soldiers’ salaries may have been augmented by additional sources of income, making service in the Roman army far more lucrative.”

The Development of Paid Soldiers

During the early Roman Republic, being a soldier was not seen as a profession. It was the duty of every man between the ages of 17 – 46, who was wealthy enough to afford weapons and armor, to serve unpaid in 16 military campaigns. These men were often farmers who would go on a campaign and then come back and work their farm.

During the 4th century BC, things changed as Rome started waging war in more distant regions. Soldiers now had to be gone from home for years at a time and would not be able to maintain a farm. In AD 6 Augustus reformed the military and started paying his soldiers 112 denarii per year. Soldiers would also get donations and special allowances from the emperor.

A good example of the buying power of a denarius is the cost of an annual diet of a Roman Soldier, valued at 60 denarii, almost half of their salary, which was deducted from their paycheck. Their salary didn’t go far, considering that during the 1st century, 27,000 square feet of farmland would cost about 250 denarii.

Later, Gaius Julius Caesar (AD 37-41) doubled the pay of a soldier and it stayed at 225 denarii per year until the rule of Domitian (AD 81-96). A centurion was the leader of 80 soldiers and received 5 times the pay of an average soldier. The highest-ranking centurion of a legion, called a Primus Pilus, was paid 20 times more than an average soldier, which was at least 4,500 denarii.

Paycheck Found at King Herod’s Masada Fortress

The soldier’s paycheck was discovered in the ancient fortress and palace built by King Herod the Great between 37-31 BC. Located on a plateau overlooking the Dead Sea in the Southern District of Israel, it was the last stand of the first Jewish Revolt, which this soldier participated in.

The devastating result of this revolt, which began in AD 66, was the complete destruction of the Jewish Temple in AD 70. The war ended at the siege of Masada, where 960 Jews committed suicide rather than be taken as prisoners.

After Jerusalem was destroyed by Rome, the remaining rebels, a group of Jewish Zealots called Sicarii (dagger-men), relocated to Herod’s fortress in Masada. In AD 72, the 10th Legion (Legio X Fretensis), commanded by Lucius Flavius Silva, marched on Masada to break the Sicarii resistance. The legion consisted of over 8,000 men, according to the Romano-Jewish historian, Flavius Josephus.

The Romans encircled Masada, constructing a siege wall that ran for 6.8 miles around the high mountain plateau. After several attempts to breach Masada’s defenses, the Romans built a giant siege ramp scaling the western side of the fortress over 200 feet tall. Then a siege tower and battering ram were laboriously moved up the ramp, and on April 16th, AD 73, the Romans breached the walls of Masada after 2-3 months of siege.

Josephus wrote that the leader of the Sicarii named Eleazar made a final speech to the defenders where he said, “…it is by the will of God, and by necessity, that we are to die” (The Jewish War, Book 7, Chapter 8 – 358). Then the defenders drew lots and killed each other in turn, down to the last person. According to Josephus, “The Jews hoped that all of their nation beyond the Euphrates would join together with them to raise an insurrection,” but in the end there were only 960 Jewish Zealots who fought the Roman army at Masada.

Conclusion

Masada’s impressive ruins are one of the most visited tourist sites in Israel. The UN’s cultural body, UNESCO, registered Masada in 2001 in the list of world heritage sites, citing its “majestic beauty” and its importance as a “symbol of the ancient kingdom of Israel, its violent destruction and the last stand of Jewish patriots in the face of the Roman army.”

Roman power had built Masada and after it was taken by Jewish rebels, the seemingly unstoppable Roman army brought Masada down. The arduous and dangerous task the soldiers of Rome had during the siege of Masada is further illuminated by the discovery of the soldier’s paycheck, which reveals the dirty work the soldier did for Rome wasn’t about earning money. He was basically a slave, following the emperor’s command to eradicate the Jewish rebels at any cost. It is interesting to note that the Roman Empire ultimately fell, but throughout history up until today the Jewish culture has been preserved.

Keep Thinking!

TOP PHOTO: A very special find – a Roman soldier’s paycheck for participating in the campaign against the Jews.(credit: Shai Halevi, IAA)